Caravaggio, whose life of transgressions often prevails over the artistic aspect of his existence, is regarded by many as the artist who captured in the subtlest way the modernity of his time. Mysterious character, still not fully known to us because of a lack of direct evidence, heirless, all we have are a few writings of his not always benevolent contemporaries. Caravaggio powerfully transmits the contradictions of a modern man with its many facets, permanently interested in making his popular soul coexist with his social growth through his acquaintances with prestigious patrons, such as Cardinal Del Monte, the Marquis Giustiniani and the Colonna princes.

These elements often clash with the circles of clerical orthodoxy, which finds his choice of popular connotations irreverent to be portrayed in religious subject.

Pursuing forgiveness for the murder of Tomassoni and therefore pardon from capital punishment and the end of exile, he leaves Naples for the Papal States, convinced by his intercessors that he can obtain indulgence. What happens next is the subject of much confusion and conjecture. He dies in 1610 in Porto Ercole, alone and miserable, hastily buried in a mass grave. Loved and celebrated in life, he is quickly forgotten, only to be rediscovered in the twentieth century.

Defined by Roberto Longhi as a “painter of reality”, his work is characterized by a direct observation of nature. Through the many contradiction of his modernity, he is the first interpreter of what will become modern painting.

When Caravaggio dies, the bishop of Caserta writes to Cardinal Scipione Borghese, collector and protector of Caravaggio, informing him of the disappearance of the artist. He mentions three paintings, found inside the boat on which he was traveling: “Doi S. Giovanni e la Maddalena” (Two S. Johns and the Magdalene).

While many copies of the Magdalene in Exctasy are known to this day, this version, authenticated in 2014 by Mina Gregori, is considered the true original; the painting he had with him on his last journey to Porto Ercole. On the back of the canvas, a note with seventeenth-century handwriting was found: “Madalena reversa di Caravaggio a Chiaia ivi da servare pel beneficio del Cardinale Borghese di Roma” (Magdalene on her back by Caravaggio in Chiaia to serve for the benefit of Cardinal Borghese of Rome)

Mary Magdalene is a repetitive presence in Caravaggio’s work, whose tumultuous life is marked by desperate attempts to find forgiveness for his crimes.

Magdalene appears on a neutral background wearing a white tunic and a red cloak. A figure of repentance, Mary Magdalene prays, her eyes dazzled by the luminous apparition of a cross wearing a crown of thorns, captured in a moment of spiritual and sensual ecstasy. Her golden hair, whose heavy mass appears at the top of the head, spreads on her shoulder and chest. Livid, the skin tones present admirable variations of color and light as shadows dominate by their intensity.

The modeling of teeth and tears running down Magdalene’s cheek are characteristic of Caravaggio as is the ear, indistinctly outlined under a carefully calculated light. The long folds of the shirt are achieved with a single broad, vigorous and free brushstroke; in the background, we can see in the darkness an entrance to a cave. A skull sustains Magdalene’s arm, signifying her departure from a life of sin.

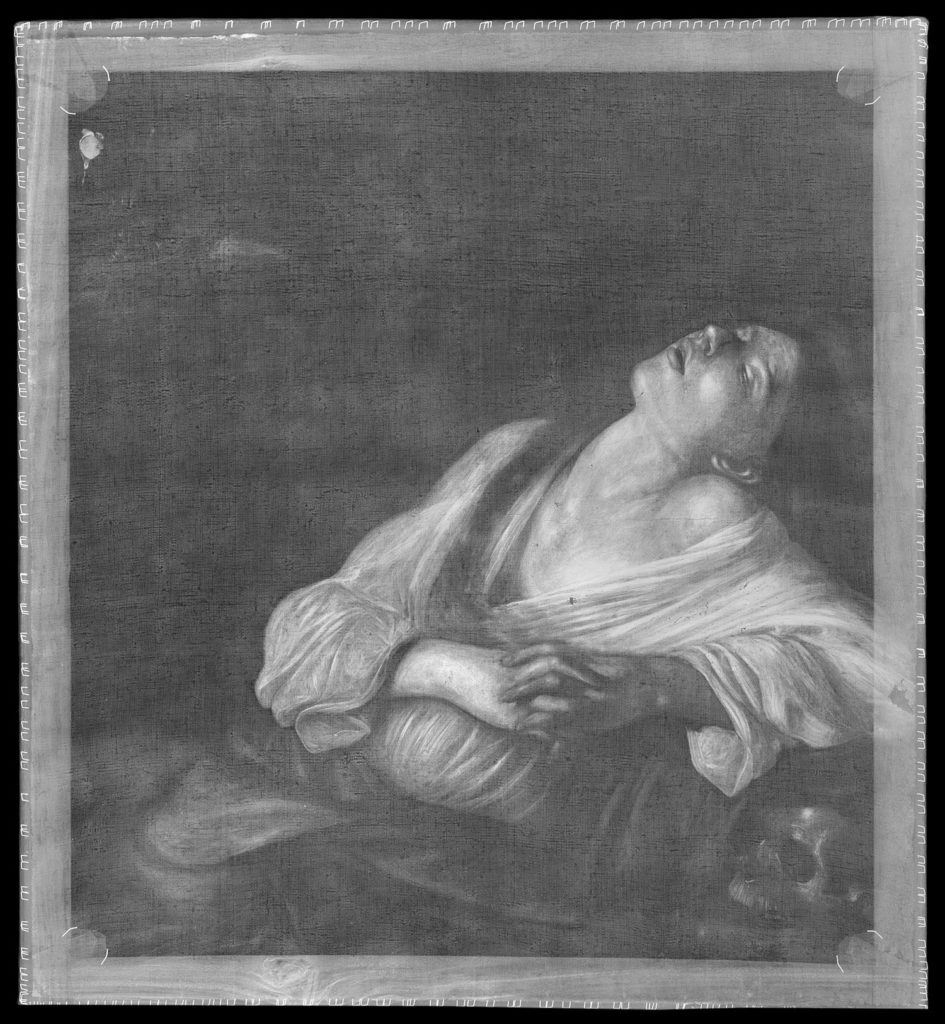

Putting together all the data from infrared investigations, acquired through our Apollo camera, and ultraviolet imaging, gives us additional information and seems to further confirms the attribution: The half-lying body of the Magdalene is not, as it appears, wrapped in a dark mass, but rests on some sort of rocks. She is framed inside a cave, whose opening is enriched by leaves and vegetation, clearly standing out in the upper left corner. Perhaps not entirely convinced of what he was doing, the artist used a light brushstroke, later deciding to hide these elements under a dark layer. Maurizio Calvesi interpreted the black background as darkness, “a symbol of evil and sin”, while the light that floods the female figure symbolizes redemption.

Certain parts, like the hair, are left in reserve and are almost not painted at all, only characterized by light reflections. We note a complete absence of preparatory drawing, with color being directly applied to the canvas. Sources state that Caravaggio did not draw but rather directly applied color to the canvas by copying from life: the frequent modifications made by Caravaggio on other of his works during the painted phase are well documented by X-ray and IR analysis and seem to confirm this fact.

The IR reflectography highlights however the presence of dark lines, preliminary to the painting, which define the profile of some elements of the composition. These lines are quite wide and compatible with a brush soaked in a dark pigment and outline the fingers of the right hand, the lower part of the left hand and wrist, the main folds of the red coat, the right shoulder and the white shirt on the right elbow. The irregularities of the surface that could suggest the use of incisions, noticeable above all for the white shirt, are actually to be attributed to the traces of the bristles of the brush.

The shape of the mouth appears to have changed during the painted phase, with a reduction of the lower lip. Changes also affect the red mantle, around the large fold near the right side, where the X-ray shows a distribution of radiopacity that is not in line with the currently visible chiaroscuro trend. More difficult to interpret is the trace of the same radiopacity of the red mantle extending from the right side, almost horizontally, towards the left edge of the canvas.

In this painting, as in the others by Caravaggio, there is art but there is also life; there is not only a formal and figurative realism, but above all, a ‘realism of feelings’, which is the great novelty of Caravaggio, especially in comparison with manneristic feelings, which were predefined. It is a deep sentimental and emotional realism because the painter identifies with the sentiment, with the psychological situation and there is this ability to represent and transmit these feelings in painting, strongly affecting us and thus allowing us to receive these emotions.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy, c. 1606, oil on canvas, private collection.

Thank you to Arcanes for sharing the imagery and write up.